I departed an all-night pool party north of the Golden Gate Bridge and rolled into the Café Bugatti in San Francisco at 7 a.m. The barista, a conspicuously beautiful red-haired girl named Sheri, banished me to a corner table because I smelled of tequila and chlorine and because I was being a nuisance trying to flirt with her during a customer rush. So I shuffled over to the newspaper rack, grabbed the San Francisco Chronicle, and sat among a cadre of curmudgeonly Italian men from the neighborhood who frequently slapped their papers and swore under their breath when they read something they disliked.

In 1989, the front page of the American newspaper was filled with stories about the Soviet Union, a country that was undergoing radical change thanks to the visionary leadership of Mikhail Gorbachev. The Soviet leader had introduced a policy of perestroika, or "rebuilding," in an attempt to revitalize his country's stagnant economy. Perestroika was fiercely opposed by many members of the Communist Party, but with the votes of the Russian people, the referendum had passed.

To thank the Russian people for their support, Gorbachev expanded civil rights by instituting a policy of glasnost, or "openness." Chief among these new rights was an expanded tolerance for freedom of speech and freedom of the press. This gave the American news agencies unprecedented access to a country that had been shrouded behind a curtain of mystery for four decades during the Cold War.

Since I had just graduated college and was on a celebratory binge that I hoped to keep going through the end of the summer, nothing of what I read about Russia was particularly interesting to me. That is until I turned the page of the newspaper.

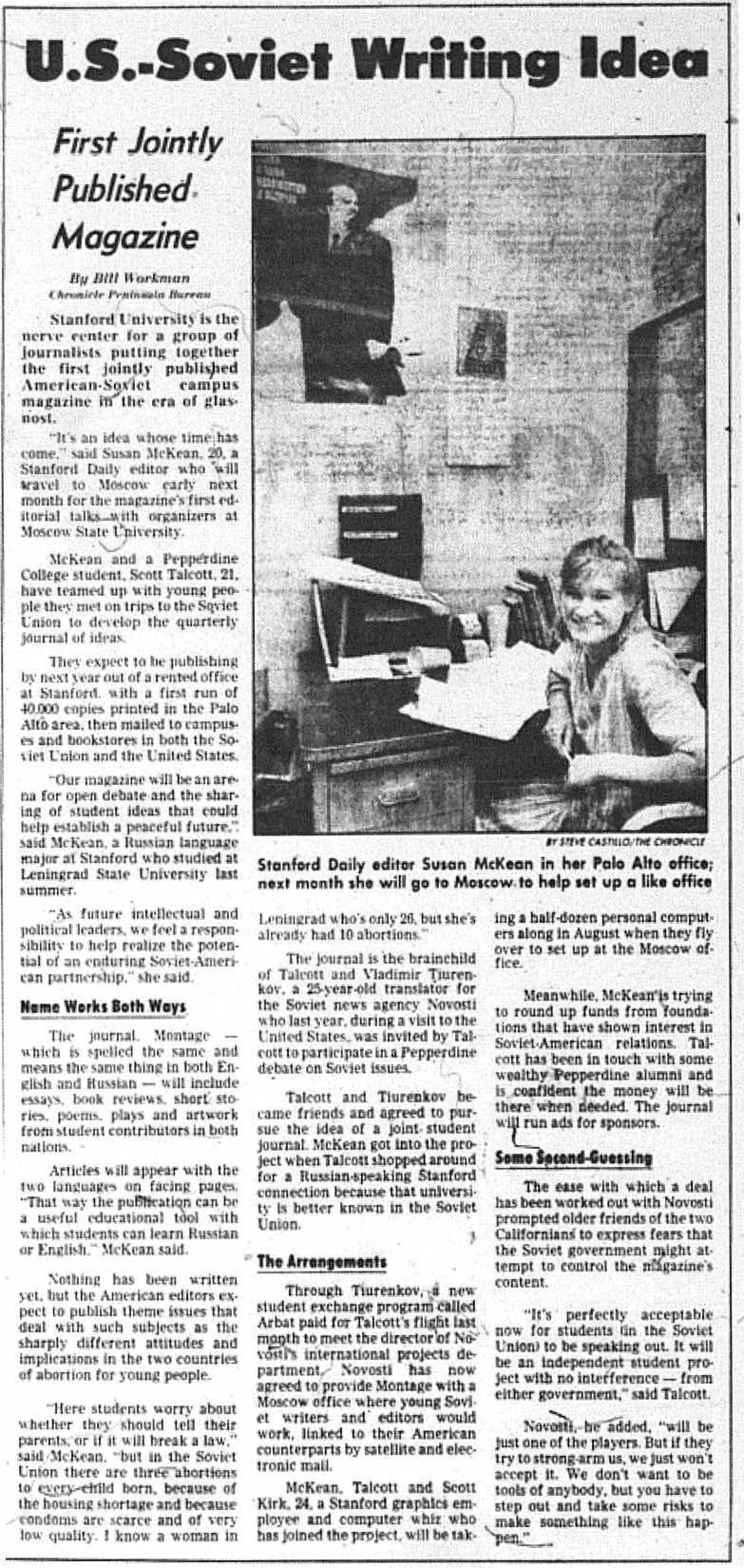

An image of a beautiful young woman sitting at a desk and looking directly into the camera stared at me. Her name was Susan McKean, a student at Stanford University. McKean and a Pepperdine University senior, Scott Talcott, had set out to create Montage, a Soviet and American magazine to be published in both countries, in both languages. The inspiration for the project was Talcott's. The previous year he had written a letter to Mikhail Gorbachev to ask for help with the creation of a newsletter about college life that would be written for students in both countries.

Many thought that Talcott's letter, although noble and well intended, was quixotic. But Talcott held fast. He truly believed that Gorbachev would reply. As proof of his conviction, Talcott and some of his fellow students at Pepperdine had kept a candle lighted at the school for fifty-two days until Gorbachev arrived in America for a state visit the previous December. Sadly, the hope of getting a response from Mr. Gorbachev was extinguished when his trip was cut short; an earthquake had devastated the Soviet Republic of Armenia and he'd had to rush back to Moscow to manage the catastrophe.

Undeterred, Talcott contacted Vladimir Tyurienkov, a 25-year-old translator for the Soviet news agency Novosti Press International. Tyurienkov and Talcott had met previously when Pepperdine University had hosted Tyurienkov to discuss and debate Soviet issues.

With Tyurienkov attached to the project, Talcott sought a partnership with Stanford University, which had a more globally recognized name and was just a few hundred miles north of Pepperdine's location in Malibu. At Stanford he found Susan McKean, a student of history and Russian language who served as the summer editor of The Stanford Daily newspaper.

According to the article, Montage had already made significant strides forward. They had assembled a staff in both the United States and in Russia. In Moscow, the Novosti Press agency had offered its resources and an office space, and in Northern California, Stanford University had done the same.

Sheri walked over to my table after the customer rush had subsided. I showed her the article and, after reading it, she said, "You should shoot the pictures for the magazine?"

"I should shoot the..."

"The pictures. The article mentions a publisher, an editor, and an art director, but nothing about a photographer."

It was an astute observation. And I was sufficiently caffeinated and sleep deprived to be fool enough to give it a go.

From the pay phone just outside the cafe I called the main number at Stanford University. A kindly switchboard operator transferred me to the Montage office, where Eric Jones picked up the phone. I managed something inane like, "You guys are awesome. I love what you're doing."

Eric thanked me for calling, and just as he politely tried to get me off the phone I blurted out that I that wanted to be Montage's photographer. He said, "The magazine hasn't thought about photography yet, and our staff positions are only open to senior-year students and those who have graduated within the past year."

Excitedly I assured him that I had just graduated from college, and that I had professional experience. Eric's tone shifted from humdrum to intrigued.

"Photojournalism experience?" he asked.

"Editorial fashion experience," I said.

Silence.

"I started in the fashion industry in San Francisco during my gap year after high school. An agent named Michael DeMartini discovered me and took me under his wing and trained me. I worked for almost three years before attending the University of Southern California." The words gushed out of my mouth like a flash flood. I closed by saying, "Location fashion photography and photojournalism are really very similar, because both genres require getting to place and creating a story with available light."

He bought it.

Two days later, I met with Eric in a small air-conditioned trailer at the edge of the Stanford University campus. Thin and good-looking with longish hair and the sensitive eyes of an artist, he was the art director of Montage. Mark Weiner, who introduced himself as the editor, had erudite eyes. He spoke carefully and deliberately. A full beard and rounded-square glasses completed his overtly academic look. Susan McKean, whose picture I had seen in the newspaper, was even more striking in person. She didn't wear any makeup, and her dirty blonde hair was pulled back to reveal angular features under a fair complexion.

Although my fashion portfolio seemed well received, Susan reiterated what Eric had said on the phone. "The magazine is in a very nascent stage, and photography isn't a priority. Our only focus is to get enough money donated so we can fly to the Soviet Union to set up the Moscow office."

"I understand," I said. "But if you can take me with you, I can help set up a system to transfer pictures and text between the Stanford and Moscow offices using the internet."

At the time, the "internet" was a buzzword for a global network that no one except collegiate computer scientists understood. I had heard about it when one of my computer animation friends in USC's Cinema School mentioned it one night over drinks. He said, "It is the coolest thing ever. You can communicate globally using a messaging service called email." So when Eric at Montage asked me what the internet was, I parroted my friend: "It's the coolest thing ever, and we can communicate with the Moscow office using a messaging service called email." It was just enough to get me a meeting with Scott Talcott, who was five hours south at Pepperdine University in Malibu.

Scott met me near the university's bookstore at a picnic table with a view of the Pacific Ocean. He unconsciously swept his Jesus-length hair behind his ears as he spoke. He seemed mildly disinterested as he looked through my portfolio, but graciously told me that I seemed to be a good photographer.

As Scott told me more about his vision for Montage, I began to understand how he had been able to motivate a group of students to keep a candle continuously lit for fifty-two days in the hope of attracting Mikhail Gorbachev's attention. He was quietly charismatic and passionate. In just a few minutes, Scott had converted me from an opportunist looking for an adventure to a true believer. I started percolating with ideas for the magazine until he told me there was no way I was going to the Soviet Union. They didn't have the money, and he didn't see the need for a photographer.

I drove back to Stanford, marched straight into the Montage trailer, and told Susan that I wanted to volunteer in the office. If I could linger just a little while longer, I could find a reason to convince the magazine to take me to Russia. Which I did, with the help of some sage advice I'd picked up in college.

In my senior year at USC, a movie producer visited our class and screened a feature film he had made. During the question and answer period, he told us a secret about how Hollywood worked. He said that despite all the complexity and absurdity, the film industry is very simple to understand; it's a business that makes money telling stories. Find a story that people will pay to see--the rest will work itself out.

That afternoon in the office, I approached Eric and Mark with an idea. I said, "The best way to kick off the first issue of Montage is to create an editorial library of photos of your first trip to Russia. The images could be used for future issues of the magazine, and, most importantly, fundraising efforts. A picture is worth a thousand words to convey what we're doing in Russia. And the pictures will inspire people to donate. You could even give a photo print to the bigger donors."

Eric and Mark both excitedly agreed that I was onto something. And they would've sold Susan on the idea if she hadn't bounded through the door with extraordinary news.

Finnair, the airline of Finland, had donated to Montage six roundtrip tickets from Los Angeles to Helsinki, only an hour north of Moscow by plane. Susan compassionately explained that there wasn't a seventh ticket for me because she had pitched Finnair about a month before I joined the group. I smiled like I meant it and promised to continue volunteering for the good of the project. Everyone thanked me for my commitment, but in truth I was in a daze of disappointment and couldn't think of anything else to say.

A few days later Russia's national airline, Aeroflot, came through with six roundtrip tickets from Helsinki to Moscow. The first issue of Montage magazine was going to come to fruition without me or my photography.

There was nothing left for me to do except accept defeat and go back to the fashion industry. Which, as my friends vociferously pointed out, wasn't exactly a bad thing. They saw me as spoiled. I had had a lucky break being discovered by a powerful agent the year after I graduated from high school. It got me an entree into one of the most glamorous and notoriously cloistered industries in the world, with a promise to continue my career once I graduated from college. Most young photographers would have given a body part to be in my shoes. And yet there I was, pining to be a photojournalist. I blame college; it had idealized me.

Michael DeMartini leaned against the edge of his desk with my portfolio in his hands. Every time he turned a page he rolled his eyes. I had been lazy with my fashion photography while I was away in school. My book was mostly made up of the photos that I had shot before college. The more recent pictures were run-of-the-mill fashion tests and other school assignment-type shots that had nothing to do with fashion.

Michael shrieked. He turned my portfolio around to show a photograph of a girl in a bikini lying on her stomach in the sand. She held her head and torso up with locked elbows and gazed longingly out of frame.

"You have got to be kidding," Michael said. "This looks like a tragic collision between a Playboy spread and a Hallmark card." He slapped my book closed and declared he was going to make me rebuild my portfolio, one model test at a time. I could see from his smirk that he was glad to see me. But he also gave me a strong word of caution: "You're not a teenager anymore. That novelty is gone. You have to compete at a very real level now. I'm gonna help you, but you best not let me down. You will shoot flawlessly, or you won't shoot at all."

I was ready. I was determined. And above all, I was thankful. The more stories I heard from my fellow graduates about the crap jobs they had to take out of college, the more reverence I had for Michael and my opportunity with him.

#

The next afternoon I drove down to Stanford to tell Susan I was not going to volunteer for the magazine anymore. I needed to focus solely on rekindling my fashion career.

I walked up the metal steps to the office and opened the door to find a celebration underway. Scott's efforts in Southern California had produced a connection with Fred Segal, the owner of the eponymous fashion retail stores in Los Angeles. Apparently Mr. Segal had a penchant for all things Russian. Once he heard about Montage, he couldn't wait to get involved. He'd put up the rest of the money for the trip.

Susan walked toward me with an arresting, wide-eyed intimacy that I had never seen from her before. She asked if I was aware that Fred Segal was also a photography collector and hobbyist. I didn't quite know what to make of her question. Before I could respond, she smiled and said, "You're going."

The following few weeks were filled with bon voyage parties, preparation, and press. The press stuff was a lot of fun. We got written up in The New York Times, Los Angeles Times, and various other news magazines. People shook our hands like they needed to know us. We got a ton of attention, even though we hadn't actually done anything yet. Such was the power of the mystery of the Soviet Union.

I tried calling Michael DeMartini about a dozen times to tell him about Russia; twice I even got as far as agency's receptionist before hanging up out of fear. By the time we settled into our luxurious seats on the Finnair flight to Helsinki, I realized that my gateway to the fashion industry was engulfed in flames. My future as a photojournalist was exceedingly uncertain as well--mostly because I wasn't quite sure what I was supposed to do as a photojournalist.

There were six of us on the flight: Scott, Susan, Mark, David, Jeff, and me. David and Jeff attended Pepperdine with Scott. They were the business side of of Montage. David, tall and congenial looking wrangled the budget while Jeff, shorter and constantly furrowing his brow in worry, headed up advertising sales. Eric would meet us in a week.

We landed in Helsinki during a biblical snowstorm. Our flight to Moscow delayed, we all piled into a couple of cabs downtown and made for a rustic-looking bar with a warm, cozy interior. In all my twenty-four years I had never seen so many striking blonde-haired, blue-eyed young men and women assembled in one place.

Susan must have felt like a den mother, traveling with five boys whose eyes just about popped out of their heads every time they caught sight of a Finnish girl. Even Mark, the most adult of us all, was having trouble holding it together. I suggested to Susan that we change Montage's tag line to "the magazine of Finland." She gave me a tolerant grin.

A few hours later, we were aloft over Russia. The dispassionate Aeroflot flight attendants rolled a metal hospital cart stocked with plastic cups, a two-liter bottle of Pepsi, and a jug of water up and down the aisle. It was my first glimpse of Communist austerity. An hour later we landed in Moscow.

#

Thanks to American propaganda, I had envisioned Russian hotels to be dull, gray, windowless cubes. Our accommodations at the Hotel Cosmos were the opposite. Built for the 1980 Olympic Games, the massive structure with 1,700 rooms looked like it belonged in Las Vegas. The decor might have been stuck in the late nineteen seventies, but the place was impressive.

When the elevator doors opened on my floor, I was greeted by a young girl sitting at a desk with nothing on it except for a telephone. She explained that her job was to route calls sent from the imposing switchboard apparatus in the lobby to the respective rooms on her floor. "Wouldn't it be easier for the lobby to send the calls straight to the rooms?" I asked.

"Then I wouldn't have a job," she said matter-of-factly.

#

I woke at 5:30 a.m. to take advantage of the sunrise light to photograph the Monument to the Conquerors of Space, which sat in a huge park across the boulevard from our hotel. Built in 1964 to celebrate the accomplishments of the Soviet space program, it depicts a small rocket atop a massive, 360-foot-tall, sweeping exhaust plume made of titanium.

I angled my camera on a tripod skyward to capture the grandeur of the entire monument. As I waited for the first warm rays of light to glint off the sculpture, I walked circles in the snow to stay warm. The freezing air made my nose run like a stream. I anxiously scanned the eastern horizon for the first sliver of daybreak. After an hour in the dark I retreated back to the hotel in a cloud of confusion, snot frozen on my upper lip.

I had made it halfway down the hall to my room before I turned around and marched up to the girl at the desk near the elevator. "What time is sunrise?" I asked. A serious look came over her face, and she picked up the phone and barked something in Russian into the handset. There was a long pause before a voice on the other end dryly responded. She hung up the phone and looked up at me with a triumphant smile. "The sun will arrive at 9 a.m."

"Thank you."

As I plodded back down the hall, the tripod in my long shoulder bag made a soft clanging sound each time it hit my hip. I vaguely recalled an astronomy class about how sunrise time is a byproduct of seasons and geography.

#

Breakfast was served in a conference room near the lobby. Susan wrote in a notebook while Scott, Mark, Jeff, and David drank tea and watched other hotel guests stride about, mostly Russian and European businessmen and beautiful Russian women in their thirties wearing expensive fur coats and fine jewelry.

Mikhail and Vladimir walked in, our Russian counterparts at Montage. Mikhail had mentioned to someone that he had a passing interest in photography, so he was nominated to be the liaison between the photography department at the Novosti Press agency and me. He wore a sweater over a collared shirt and gray-blue slacks that looked just a little too long for him. With his laissez-faire disposition and slightly receding hairline, he looked older than his late twenties.

Vladimir, who insisted that we call him by his last name, Shchukin, was confident and savvy. His angular features, steely blue eyes, tailored clothing, and "no problem" responses to all of Susan's logistical concerns--no matter how complicated--supported my hunch that he was a connected politician and not really a publisher.

After a few minutes of "Hi, how ya doin', good to know you," exchanges, Shchukin made an announcement: No circulating American currency in the Soviet Union. The US dollar was very valuable in Russia's black market. It was considered a "hard currency," because it was traded on the foreign exchanges and used as the standard for global transactions. On the other hand, the value of the Russian ruble, a soft currency, was controlled by the Soviet government. To spare us the temptation of interacting with the black market, Shchukin handed each of us an envelope bulging with rubles to spend as we needed. If we ran out, we were to see him about getting more, "no problem."

We piled into two cars that came with drivers to make our way to the Novosti Press building, where we were going to set up the Montage office. But first, at Shchukin's suggestion, we made a quick tourist stop at the Monument to the Conquerors of Space. As we all looked up to take in the spectacle of the sculpture, Shchukin suggested that I take a picture. "Great idea," I said. I stood about two inches from the footsteps I had made that morning, angled my camera skyward, and shot an unremarkable photo.

When the American Montage staff walked into the dark, wood-paneled, cigarette smoke-filled conference room at Novosti Press International, we were welcomed with polite applause. Scott, Susan, and Mark sat at a large hexagonal table with the Russians. Ideas for the magazine were bandied about in two languages. Susan struggled to keep up with translating. Scott whipped his head back and forth trying to make sense of what was going on. And Mark sat contemplative, his folded hands holding up his chin. Jeff, David, and I lingered in chairs against the wall, watching the chaos unfold. After two hours of a lot being said and nothing being decided, I escaped to the streets of Moscow to shoot pictures.

#

Given the number of people walking around, it was eerily quiet. Each time I approached someone to take their picture, I was given a spine-tingling scowl. One elderly woman raised her cane, threatening to hit me. A young girl, who was agreeable to having her photo taken, was quickly eclipsed by her six-foot-four father. He placed his hand over my lens and barked something in Russian that I was glad I didn't understand.

The only halfway decent photo I took was of the ice floe on the Moscow river--almost good enough for a greeting card. I walked back to the Novosti building, deeply frustrated.

#

The cloakroom in the lobby of the Novosti building was so full that metal garment racks were lined up along the wall outside the door to accommodate the overflow. The coat-check operation was run by two robust, elderly women with mustaches. The one with a blue cardigan casta suspicious eye on my fancy down jacket, which looked decidedly different from the long wool coats everyone else wore. She hissed something in Russian as she handed me a claim ticket.

A woman's voice behind me said, "She doesn't like your jacket."

I turned around to see a tall, slender woman with dark eyes and short dark hair, about my age. "Is that what she said to me?" I asked.

"No, she said something worse."

"About the jacket?"

"No, about you."

"Do you think she knows I'm not from Russia?"

Lada Leshchinskaya laughed. She told me that she worked in the building and had heard American journalists were coming to town. I asked if she wanted to meet for coffee later. She said that Russians preferred tea, but that getting together would be "convenient."

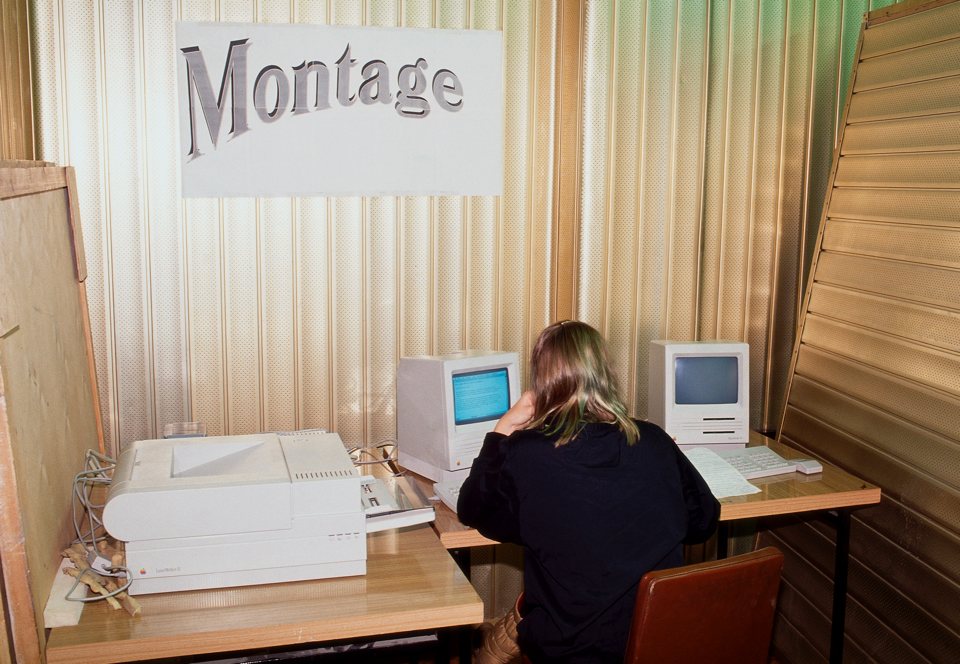

Two tables were pushed up against each other in an "L" configuration. Two Macintosh computers and a laser printer, all donated by Apple, were set on the tables and switched on. Someone taped a laser-printed banner proclaiming Montage to the wall, and the Moscow bureau of the magazine was born. It may have been unglamorous, but it was awesome all the same. It inspired me to go out and find some good photographs.

#

After riding two subway trains, Mikhail and I arrived at a "typical" Moscow neighborhood. It was mostly tall, gray apartment buildings that all looked similar to each other in the bright light of a cold, clear day.

As we walked, Mikhail asked me what I wanted to photograph. It was an excellent question. The reality is that the day-to-day activity of most people in any country is totally mundane. Mikhail tried his best to point out some potentially interesting shots, like a woman carrying groceries. He went up to her and explained that I was a photographer and asked if I could take her picture. She agreed, and the very uninteresting "woman carrying groceries" was immortalized on film.

I appreciated Mikhail's efforts. He was trying to find relevance in his role as the photo liaison to American photographer, just like I was trying to find relevance as the photographer from America who had no idea what he was doing. We would both have been better off at a pub drinking and exchanging hyperbolic stories about our college years.

Mikhail excused himself to go find a bathroom while I ventured on toward the sound of children playing. In the long shadow of one of the apartment buildings, I found a playground. Kids were racing around and throwing snowballs at each other while their parents were huddled near a jungle gym. Occasionally one of the adults would lean out of the congregation and yell something at a misbehaving child, which elicited smiles and comments from the rest of the adults.

I took a picture of the kids. It was sweet, but pedestrian. The image could have been shot in Moscow or Minneapolis. Then I saw two men standing at the other side of the playground. One was young and blonde and tall. The other had dark hair, thick-rimmed glasses, and a Lenin beard tinged with gray. Their coats were noticeably nicer than most I had seen around Moscow. They talked close to each other and furtively passed envelopes back and forth.

I moved slowly toward the two men, occasionally stopping to take a picture of a treetop, as if to say, "Who, me? Don't mind me, I'm just taking pictures of barren trees." When I got close enough, I brought the camera to my eye and pointed it at a parked car. Then I slowly spun to the right until I found the two men in the viewfinder. They were walking toward me. The shutter clicked and I ran.

Each footstep sank a little into the snow and my heavy camera bag threw me off-balance each time it banged against my hip. I felt like one of those animals on a nature show just after it gets shot with a tranquilizer dart. By the time I rounded the corner of an apartment building, I was totally winded. After a few labored breaths, I peeked back around the corner and saw my pursuers laughing hysterically, with Mikhail.

Mikhail beckoned me from my hiding spot with a wave of his hand. He introduced me to Alexei and Gregor. They thought I was a government official keeping an eye on them. "You mean like a KGB agent or the police?" I asked. Everyone laughed out loud again.

"No," Mikhail translated, "more like a bureaucrat. A KGB agent would never be so obvious."

Alexei and Gregor were engaged in the black-market trading of American dollars, a crime that was mostly overlooked by the police. At least it had been for years, until Russia took its first baby steps toward a Western-style democracy. Gregor said some of the cops, loyal to communism, were becoming more rigorous about petty crimes. It was a way to express their discontent about the new political direction of the Soviet Union.

"So you're glad I'm not a cop," I said. There was more laughter. I started to laugh too, not because I was in on the joke, but because there was nothing else to do.

When Mikhail and I said our goodbyes, Alexei and Gregor each gave me a bear hug. It was a recurring quirk with the Russian people; on the street the mood was cold, but once you got to know anyone, you were practically family.

Alexei and Gregor told me to learn the Russian phrase for asking to take a person's picture to avoid any further misunderstandings. I presented their suggestion to Lada later that day, when we met for our tea date. She wrote down the phrase in my notebook and then made me practice it over and over as we walked to the subway. By the time we surfaced near Red Square, I felt like I had a reasonable handle of the pronunciation, which sounded something like "mojno vas fotografiya, pajowlsta."

#

I had seen Red Square on television dozens of times as a stage for military parades, but it looked totally different in person. The fanciful onion domes of St. Basil's Cathedral stood in stark contrast to the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier and the imposing red brick wall of the Kremlin across the square. Entombed in the middle was Vladimir Lenin, still holding court as a corpse.

The sound of clapping boots on cobblestone echoing through the square caught my attention. Three soldiers marched toward Lenin's tomb in flawless synchronization. Two of the soldiers marched up to the guards already standing next to the tomb and faced them, nose to nose. For a minute, nobody flinched. Then, just as the first bell of the hour rang out from Spasskaya Tower and with the precision of a Swiss watch movement, the relief soldiers spun into place and the original soldiers spun out. The relieved soldiers raised their guns and joined the waiting third soldier, who marched them back to the tower. It was a mesmerizing display of grace and discipline.

I set up my tripod and took a picture of the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier. The lonely dancing flame against the massive Kremlin wall was haunting. It my first decent photograph in Russia.

Lada led me down a narrow street that took us out of Red Square. I saw clouds of steam belching from between two buildings. "Moscow is dotted with massive facilities plants that boil water to heat the apartments, shops, and offices," Lada said. "The water gets distributed through a vast subterranean network of aging pipes. When any of the pipes springs a leak, the hot water combines with the cold winter air to make huge clouds of steam that seem to come out of nowhere."

As I watched the steam swirl and dissipate under the light of the streetlamp, a well-dressed businessman stumbled out of the mist and plodded up to the corner of a building and patted it. Satisfied that it wasn't going anywhere, he leaned his full weight on his outstretched arm, his body at an angle. It was like watching a ballet dancer getting into first position. Then, without any ceremony whatsoever, he pointed his head at the ground and vomited into the snow.

A few yards down the street, a man swerved into us, happily singing a slurred version of a Russian love song. Lada explained. Various shortages of food and sundries plagued Russia and its ailing economy, which also affected its vodka supply. On the rare occasion a shipment of vodka did make it to the sparse market shelves, it sold out in hours and was consumed almost as quickly.

"It is the way some Muscovites cope with the long nights of winter," Lada said.

She also shared that the state handed out antidepressants in the office buildings every Tuesday and Thursday to keep winter depression under control.

"It sounds a lot like Beverly Hills, except that the state doesn't supply the meds," I said.

"Why would such a sunny, happy place require antidepressants?" she asked.

"The land of plenty is just too plentiful for some."

#

Before Lada could walk through the door of the Hotel Cosmos she had to stand in line to show her ID at a special entrance that had a window with thick glass and a circular vent mounted in the middle, like the kind you see when you're buying a train ticket. It was the Soviet answer to controlling young courtesans and husband seekers who loitered around the foreigners drinking in the hotel's lounge. The annoying formality served only to inconvenience people like Lada who wanted to get a drink with her new American friend. Bribery and physical favors ensured that those who were meant to be kept out had easy access.

When Lada made it through, we settled in to the lounge. She gave me a few more Russian phrases to learn. (Dobre utro!), "good morning," (Dobre dien!), "good day," and (Dobre vekyer!), "good evening." I enthusiastically repeated them a few times.

Then she taught me something a little more complicated. The ever important (YA ustal, kak sobaka) which means "I'm as tired as a dog"--good for retreating from boring parties and long-winded editorial meetings. When I got my tongue around that pronunciation, she had me try something else. It sounded similar to the "may I take your picture please" phrase she had taught me earlier. Instead of the word (fotografiya), she instructed me to say (potseluy). I repeated the phrase a couple of times as best I could. Lada laughed at me and then leaned in close: "May I please have a kiss."

#

When it came to social obligations, the Montage staff was divided up into two teams of three to help prevent burnout. As the official photographer, I had to attend everything. I was getting spectacularly good at shooting grin-and-grab photos. Sadly, in the history of photography, no one has ever won an award for capturing a group of people grinning for the camera while clutching their cocktails.

I was in a rut, my romantic perception of photojournalism evaporated. I missed the "glam slam" of the fashion industry. The hot women, the warm studios. The disingenuous clients, the constant pressure to produce trendy, cutting-edge work, only to have it criticized into oblivion by halfwit wannabes slithering along the edge of the industry... Maybe I had to give photojournalism another chance.

I asked Mikhail to take me back out to the streets of Moscow, "maybe someplace a little more lively than last time," I said. He shot me a look that clearly implied I was an asshole.

"You asked to be taken to typical Soviet neighborhood."

I backpedaled. "Yes. That's true. I did. But this time I need a place with a little more verve."

Mikhail had no idea what "verve" meant, and I had no idea what I was asking for. We silently looked at each other for a few seconds before he bid me to follow him to the Novosti photo department.

The images that hung on the walls were extraordinary and intimidating, flawless storytelling in every frame. Each of the photos evoked a deep, visceral reaction in me that took me by surprise.

I thought back a few months to when I'd told Eric that my experience as a location fashion photographer had given me the chops to be a photojournalist. I'd said that being practiced in creating a story from an environment, a model, and a pile of clothes would be enough. As I stood in the shadow of the hanging work of the Novosti journalists, I knew that I had got it very wrong.

Vladimir Vyatkin walked into the room. He was a legendary award-winning photojournalist, and the head of Novosti's photo department. I was scheduled to meet him and the other staff photographers in a few days' time for a social get-together and portfolio exchange. Back in the States, I had prepared a mini-book of my fashion work just for the occasion. I wished I hadn't. It was destined to be laughed at when compared to the indelible images that surrounded me.

Given his renown, I had imagined Vyatkin would be standoffish and aloof. In fact, he was quietly avuncular. He had unkempt salt-and-pepper hair and a Van Dyke-style beard the same color. He looked like a confident, rebellious bohemian.

Mikhail introduced us. Vyatkin was a passionate photographer. He believed in visual storytelling above all else. He used a Russian-made camera that was the epitome of basic, yet the pictures he produced were leagues better than I could ever dream of shooting. My new camera gear, which I had bought specially for the trip, now seemed conspicuous and I felt rather like an undeserving fraud.

Vyatkin asked for the first roll of film that I had shot in Russia. He was going to have it processed in time for the get-together with the other Novosti photographers. I tried to resist; the outing with Mikhail to the "typical Soviet neighborhood" hadn't exactly gone so well for me. But Vyatkin was insistent. He said he wanted to see an American's first impression of his country. I reluctantly put the roll of film in his hand, and he immediately passed it to the lab assistant who was hovering around us. It would take about four hours to process the film and hang it in the film dryer, where anyone could see it. I figured I'd be a laughingstock by teatime.

#

Jeff, David, and I were invited to a party at Moscow State University. We entered a large room with a long table, surrounded by twenty or so students. As soon as we sat down, we were each presented with a large mug filled partway with Czechish beer. We were told, with a tone of pride, that the beer had been smuggled into Russia inside some perfectly innocent-looking gas cans. We were each handed a shot glass filled with vodka and instructed to drop it into our beer mugs. As the concoction bubbled up, we quickly chugged the whole thing down to a cacophony of cheers.

After a half hour of conversation and few more beer-vodka bombs, I was lured away from the party by a well endowed girl with short brown hair and blue eyes named Diana. We found a dark stairway landing and made out. Which led to her shirt coming unbuttoned, and my awkward grappling with a serious bra hook. We kissed some more. Then she pulled back, smiling. As she sat topless, she gazed sincerely into my eyes and asked me to marry her. I later wondered if for Diana, the encounter was neither lust nor love--it was a strategy to get out of the Soviet Union. At any rate she remained utterly expressionless when I nervously suggested that we reassemble ourselves and go back to the party.

#

The crowd of drinkers had thinned out considerably. Jeff, with red cheeks and slurred speech, was holding court at the end of the table. David was missing.

As I made my way down the hall to the bathroom, a blast of cold air hit me. I peered into a darkened dorm room to see a window flung wide open. A body teetered on the sill with head hanging outside and feet dangling inside. It was David. Two stories down, a puddle of vomit had melted through the thick layer of snow to the pavement. I tried to cajole David to come in, but he insisted the cold air felt good on his face. I said I'd be back to collect him after I went to the bathroom, and suggested that he not fall out while I was gone. He thanked me for the safety tip.

The next day at breakfast, Jeff, David, and I searched each other's faces, hoping that one of us had the explanation of how we'd all made it back to the hotel the night before. No one did.

#

I was discovering that photojournalism is a real slog, an exercise in monastic patience while waiting for something photo-worthy to occur. The tedium of visually documenting mundane social events, from sightseeing expeditions to a basketball game-cum-grudge match between the American and Russian staffs of the magazine, was getting to me. I worried that I had deceived myself as well as the Montage staff. Adding to my malaise was the knowledge that my disastrous first roll of film had been processed and had no doubt become the stuff of legend.

For days I fantasized about hitting the streets to shoot something journalistic like the work that hung on the walls of the Novosti Press office. Something I could bring to the get-together with Vyatkin and the other Russian photographers, to show them I wasn't hopeless. But the social schedule of the magazine staff was too hectic and the daylight hours too few to allow me the time to venture out on my own. I was doomed to be outed as a fraudulent photojournalist who carried a fashion portfolio in a town without a fashion industry.

My anxiety was threatening to smother me by the time Susan announced a field trip. We were to visit one of oldest Russian Orthodox churches in the country.

Mikhail Gorbachev's new policies had lifted a decades-old state ban on religion. The churches, expropriated during the revolution, had lately been returned to the clergy. This had all the makings of an iconic image: history, beauty, and faith. As far as I was concerned, it was a divine intervention, a reprieve, an opportunity to shoot something compelling on the eve of the portfolio exchange.

I asked Mikhail to go to the photo department and ask how late the lab techs would be working. When he returned to say past midnight, I knew fate had tipped its hat in my direction. I'd shoot some great photos at the church, hustle back to Novosti, and have the roll rush-processed in time for the photographers' meeting.

#

The sun slid between barren trees, casting amber streaks on the snowfield that surrounded the old church. Inside, the sanctuary was lit solely by candles and the air was heavy with the smell of incense. Parishioners stood silently in a nave without pews while a rotund priest, tented in ornate robes, said mass. It was a scene straight out of a journalist's dreams; ethereal, evocative, and timely.

I spotted a balcony that offered a fantastic vantage point for the perfect photo. On the way to the stairs, I passed two soldiers smoking next to a partly open church door. They gave me an acknowledging glance and continued with their conversation. It never occurred to me that they would question who I was, or what I was doing. Perched on the balcony, I pulled my tripod out of its canvas bag just as both soldiers burst through the doorway and startled the shit out of me. I lost my grip and the tripod landed with a metallic clang that echoed throughout the church. The soldiers confiscated my photography gear for the duration of the mass.

#

The next day I arrived at the Novosti lab for the photographers' get-together with nothing to offer except my fashion portfolio. Vladimir greeted me enthusiastically and introduced me to the two Russian staff photographers, Eduard and Viktor, who looked to be in their late twenties, just a few years older than me. We all sat down and exchanged portfolios. As I paged through their extraordinary photojournalistic images, I glanced across the table to see how my work was being received. Everyone was smiling. But then, there's not a male on the planet who's going to look at a collection of beautiful models and scowl.

Tea was served and we started trading how-I-got-that-picture stories. Eduard said he was once run down and detained by the military when he pushed too far beyond a crowd barrier. I followed with the time a makeup artist, a model, and I got chased, with dresses flying like flags, from the protected wetlands around the old Hughes Airport runway near Santa Monica. It took a few seconds for the story to translate, but it eventually got a laugh.

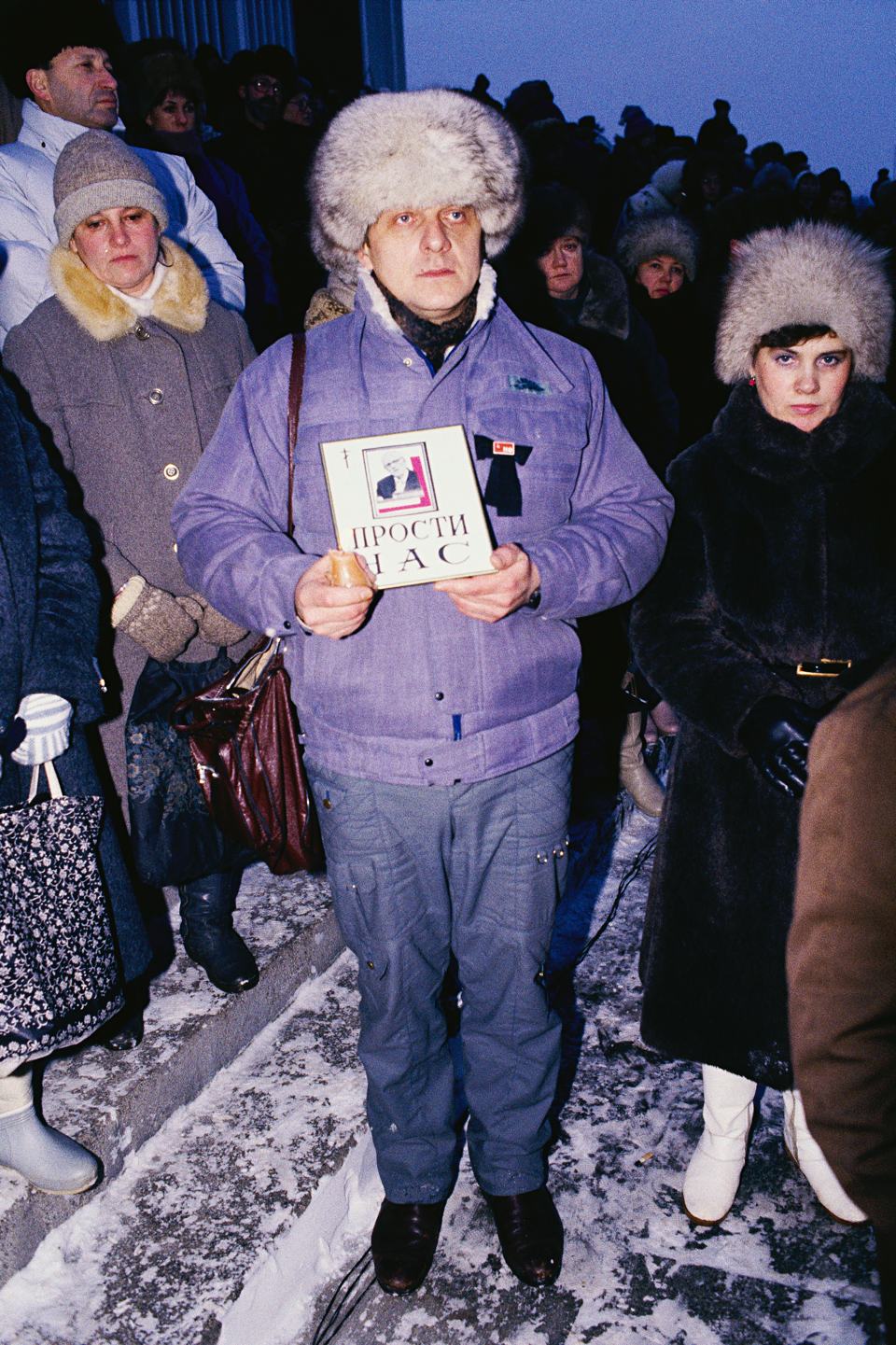

As the stories continued, there was a growing and welcome sense of camaraderie between all of us. I was feeling pretty good until the lab assistant walked in to announce that my roll of film, the roll I had given Vladimir a few days earlier, was ready to be viewed in the light table room. Eduard and Viktor pushed out their chairs, but Vladimir bid them to stay seated so that he could tell us how Andrei Sakharov had died during the night.

Sakharov was a nuclear physicist, an innovative designer of thermonuclear weapons, and a hero to the Soviet military. One morning he woke up and decided there had to be more to life than dreaming up ways to vaporize people. He started crusading for human rights, civil liberties, and publicly speaking against the Soviet involvement in Afghanistan. He became a hero to the Russian people. The Soviet government--none too pleased that their star military scientist had suddenly found a conscience--banished Sakharov to an apartment in the small city of Gorky, where he remained until his death.

In central Moscow the police had been called out to monitor a rapidly growing crowd of Sakharov mourners. Vladimir told us we were all required to photograph the impromptu memorial gathering. But, he warned, we should keep alert for any altercations that might crop up between the police and the crowd. The communist factions within the Soviet government were at odds with the majority of Muscovites, who were looking toward a democratic future for their country. An undercurrent of tension was coursing through Russia. A simple tussle could easily escalate into a runaway civil disturbance with the potential to ignite into something violent. When he dismissed us to get our cameras, I snuck into the light table room to look at my film.

The picture of the kids playing wasn't all that bad, but the work went precipitously downhill after that. There were a few half-assed pictures of barren trees, a parked car, and a frame with two blurry blobs that looked like a sad attempt at a fake Bigfoot sighting. Vladimir came up behind me. He laughed and said, "This is your first impression of Russia?" I tried to conjure up some sort of excuse, but before I got anywhere Vladimir grabbed my shoulder. He laughed again and told me not to worry.

"I feel like a fraud," I said.

Vladimir gave me a puzzled look and I did my best to explain what "fraud" meant. He told me that I was a decent photographer, but that I didn't know how to recognize a story. "If you can't see what to photograph, how can you photograph it?" His logic was undeniable. "Photojournalism is a skill that needs to be practiced, and the only way to practice is to go out and shoot pictures. You always must go out. If it's interesting, if it's not interesting, it doesn't matter, you always must go out."

I felt relieved. I wanted to hug Vladimir. I wanted to hug the lab assistant. I wanted to call the other Novosti photographers into the room, show them the crappy film, and then hug each of them, too. That's when Vladimir chuckled and told me that I shouldn't be so forthcoming with my bad work. "A good photographer knows how to hide his tragedies." Then he handed me the scissors and said, "Every one of the photographers on this wall," he pointed at the hanging images, "had a film like yours that no one has ever seen." He smiled and walked away. I cut the one good frame of the kids playing out of the strip of film, and turned the rest into confetti.

Hundreds of people had gathered at the plaza in front of a tall government building. Their mood was somber. Some held pictures of Sakharov on their chest, some held lighted candles. For the first half hour I shadowed Vladimir. His method was simple: He kept his camera out in front of him, he constantly scanned the crowd, and he only approached people with whom he first made eye contact. He told me that if you keep a sharp watch, you can often see situations developing.

Instead of lugging my large camera bag, I took to carrying one camera just like Vladimir and the others. My movements were much more agile in the tight confines of the dense crowd. I was forced to use just one focal length of lens, which, as it turned out, is an epic way to learn how to be visually resourceful.

I'd catch someone's eye, give them a little nod and a smile. If they nodded back, I took their picture. Sometimes I tried the Russian phrase that Lada taught me. It usually got a laugh followed by the proper pronunciation, which ultimately provided an opportunity for another photo. It was a valuable lesson in working with what you have, even if what you have is very little.

The police cordoned off an area halfway up the steps. It looked like an impromptu stage was being set up. With colon clenched, I walked with a purposeful step through the police line in plain view of three officers. One of the cops yelled at me in Russian. When I held up my camera and said, "Novosti, Novosti," he waved me on. I was shocked.

From my high vantage point I could see a widely diverse crowd. All of them seemed profoundly affected by the death of Sakharov. He had relinquished his position of privilege and defied the government so that he could pursue the path he thought was best for the Russian people. He was a true revolutionary.

When we got back to Novosti, Vladimir congratulated me on a good day's work. I told him that I didn't shoot anything particularly brilliant. He smiled and said, "You went out. That's the job. You must always go out."

#

The next morning, Susan and I were in the backseat of a car stuck in a traffic jam when a news bulletin was announced on the car radio. Susan stared at the dashboard speaker, and I stared at Susan. Communism had collapsed in Romania. All the other cars around us honked in celebration. Our driver opened his window and pumped his fist in the air. The jubilation lasted for a few minutes, and then abruptly stopped. It was still dangerous to speak out against communism in Russia. Susan told me the story of what had happened to Nicolae Ceausescu, the Romanian leader.

A few days earlier, in the Romanian town of Timisoara, a small group of people had gathered to protest the government's eviction of a Hungarian pastor who had spoken out publicly against the Communist leadership. They were joined by a group of students who started shouting anti-Ceausescu slogans, which spurred more townspeople to add their voices to the rebellious chorus. The small protest became an uprising.

Ceausescu was in Iran at the time, which left his wife with the authority to subdue the disturbance using water cannons and tear gas. When Ceausescu returned to Romania, he put together a fake pro-government rally by paying factory workers to make up a crowd in front of one of the public buildings. Ceausescu was going to speak from a balcony, and the workers were meant to cheer him on. It was an illusion for the TV cameras, to show he still had the support of the Romanian people. This strategy had managed to quell unrest in previous years; however, this time was different.

Barely eight minutes into Ceausescu's speech, a few dissenters started to yell anti-government slogans. Soon the entire crowd, including those who had been paid, turned against the Romanian leader. Ceausescu and his wife barricaded themselves in the building to survive the night. They fled the next morning in a military helicopter that plucked them directly off the roof.

#

At Novosti the atmosphere was frenetic. Telephones rang, people hurried through the hallways, and the photo department was uncomfortably warm as the film and print processing machines operated at full tilt.

Vladimir called all the photographers together. "Go out and photograph the people's reaction to Ceausescu's fall. Photograph the mood of Russia," he said. I ran to the elevators.

Outside the Novosti building I took a few steps up the street, stopped, turned around, took a few steps the other way, stopped, and turned around again. I had no idea where to go. After a few minutes' deliberation in the warm lobby of the Novosti building, I decided to go to Moscow State University to find English-speaking Russians in my age group.

#

I connected with a group of students in a hallway of the university. They spoke enthusiastically about the opportunities a democratic Russia would bring. But there was concern about democracy growing too quickly. "Wouldn't the rapid expansion of democracy be a good thing?" I asked. A rosy-cheeked man who was a graduate student explained the complicated reality.

Nine months earlier, the first democratic parliament in Russia's history was elected. On the surface this seemed like a triumph for Gorbachev's reforms, but the Communist Party--Gorbachev's party--saw it as alarming. Perestroika and glasnost were viewed as experiments meant to help the flagging Russian economy, not a new style of governing.

If the Communist Party felt their power eroding too quickly, there was a strong possibility they'd react by deploying the military to regain control. Unlike the police in Romania, who were easily overcome by the citizen protesters, the Russian military was the second most powerful armed force in the world.

One of the students asked if everyone sitting in our circle would be willing to fight for the new democracy. There was silence. It was a heavy question. Fighting for a new democracy would pit Russian against Russian, citizen against military.

One of the young women in our group spoke up and asked, "Why does everything have to be considered in terms of such violence?" She offered a more sensible version of the question: Would they all stand together to protest? Everyone readily agreed. One young man pumped his fist in the air for a second, then feigned cowering. He pretended to look around to see if the KGB was surreptitiously watching. Everyone laughed.

Another young man scowled. "This is serious business we're discussing. Look at how the Romanian army shot and beat the protesters in Timisoara," he said. Then another student said, "Ceausescu is an evil man. Gorbachev will never allow that to happen."

I sat and listened long enough for an empty Pepsi bottle to become filled with cigarette butts. When I left, I walked around to the front of the school and down a tree-lined promenade that stretched for almost a half-mile from the front steps of the university to the Moscow River. The rules of engagement for photojournalists haunted me as I walked. I tried to piece together some sort of ethical code, but I couldn't find a reasonable reconciliation between responsible journalism and my version of responsible humanism. As the freezing wind bit my cheeks, I imagined myself photographing a crowd of protesters. Then I envisioned the military shooting into my imaginary crowd. Would I run? What would I do if one of the students I just met was bleeding at my feet? What would a seasoned journalist do? Shoot the picture and then let the person bleed to death? I wasn't sure I could be that detached.

I walked for a while in a pensive fog, until I came upon a husband and wife teaching a group of teenagers to cross-country ski in Gorky Park. Everyone was laughing and having a good time as the students struggled to stay upright on their skis. The scene, in all its quotidian normalcy, struck me as remarkably precious--especially in the context of the political conflict that simmered beneath the surface of the country.

When I exited Gorky Park I found myself on a snow-covered street, trying to make a best guess as to the direction of a subway station. I walked toward the din of traffic and saw huge puffs of steam billowing from the street grates. Without thinking, I raised my camera and shot a photo of a group of Muscovites. They were walking directly into the clouds of steam. The sun cast their long shadows toward me on the snow.

I made it back to Novosti just after sunset. I tried pitching the image of the husband and wife ski instructors in Gorky Park for "the mood of Russia" assignment. But Vyatkin wasn't having it. He placed his hand firmly on my shoulder and said, "A photographer always goes out. Even if he brings back nothing, he always goes back out the next day. It is a game of persistence. Of always being there with your camera." Then he smiled. "You need to go back out tomorrow."

I asked Vladimir about the ethical dilemma rolling around my head. "Ah," he said, "that is a constant struggle." He led me to another room and rooted through a stack of black-and-white prints until he found a picture of a young girl who looked about nine years old. She lay dead, covered in a thin layer of ash-colored dust from a bomb blast. Her eyes were open and shiny and reflected the gray sky above her, which, Vladimir explained to me, meant she had lived for a few moments after the blast. A wave of profound sadness swept through my entire body. The little girl had died scared and alone. I could feel my breath deepen with protective anger for her.

Vladimir said, "This disturbing image affects everyone who sees it. It has the ability to move governments to intercede. That is the power of photojournalism." Then he asked, "What would you have done if you came upon her and she was still alive?"

"I would have helped her," I said.

"Then you would cease to be a journalist."

I stared at the image, lost for words. Vladimir broke the silence and said, "Then it is not so much of a dilemma for you."

I asked what ultimately happened with the photograph. Vladimir regarded me with sad eyes. "Politics kept the picture from ever being published."

"That. Sucks." I was incensed.

"It is a reality we all face. There are no rules, there is only your heart. You must do what you feel is right and always remember, the journey to the truth is never obvious." He gave a soft punch to my chest. "You have a good heart. You will be fine." He was called away. I stared at the picture of the girl again. Tears welled up in my eyes. I wiped them and looked around to see if anyone was watching. My eyes welled up again.

#

For the remainder of my time in Russia, I was never without a camera. I kept it slung off to the side so it wouldn't be obvious, but it was always accessible. I shot a lot of really mediocre photos. But then, every once in awhile, a great one.

It was 4 a.m. in Leningrad. I couldn't sleep because the dorm room Mikhail and I shared was bitterly cold. Outside our window, a few of the windows in the building next to us suddenly glowed orange as the lights inside were turned on. I set up my camera on a tripod and took a series of long exposures. The color contrast of warm windows against the cool blue of the winter morning perfectly illustrated my perception of the Soviet Union.

I came to learn that each photo, bad or good, was a stepping stone of experience. The more experience, the easier it was to recognize when a picture was about to come together. It's like when you stare out at the ocean enough times and instinctually begin to see which swells will become good waves. I also learned that there are no shortcuts to gaining experience. Like Vladimir said, the only thing to do is always go out.

#

My last night in Moscow, Lada and I went on a proper date. I took her with me to the celebratory dinner for the American and Russian Montage staffs, which the Americans paid for with our free rubles. Instead of taking one of the cars back to the Hotel Cosmos, Lada and I walked so we could have more time together. I was going to miss her. I felt it in the pit of my stomach. I was going to miss Russia too.

I discovered that communism was just one facet of Russian culture, not the whole picture as portrayed in the States. The Russians were passionate and proud, with a rich history fueled by an occasional revolution.

In the shadow of the Conquerors of Space monument, under a bright moon, Lada and I said our goodbyes. I could tell that Lada thought the location was cheesy, but it was the only semi-romantic place I could think of and she was kind enough not to make fun of me for it.

She gave me a Russian lapel pin that depicted a runner with the Olympic torch to take back home with me. I gave her the digital watch that had woken me up four hours too early for sunrise on my first morning in Moscow. We said goodbye with a few tears and a lot of kisses.

#

From my hotel room window high above the streets, I could see a white car, a Volga, broken down with its trunk open. Across the boulevard, a man held his hand out to another Volga, hoping for an impromptu taxi stop. I never did find the photo that captured the "mood of Russia." I failed the assignment, but I had gained a mountain of knowledge in trying. I came to understand the essence of photojournalism. It is patience, observation, and skilled photographic reaction. One has to develop a mastery for seeing that something is about to happen a split second before it actually does, all while floating in the shadows to avoid being noticed. A photojournalist has to be half monk, half observer, and all storyteller.

I turned off my room lights, diminishing their reflection in the window, and brought out my camera for one last picture of Moscow. I knew that if democracy flourished, the boulevard outside my window would soon look radically different. The poorly made, constantly breaking-down Volgas manufactured by the state would be replaced by familiar marques like Toyota and Volkswagen. The dull gray Russian shops with their empty shelves would be replaced with glitzy brand names of the West. Moscow would soon emerge as a modern city. In my heart I felt this would be a good thing, but at the same time I felt that something remarkable was about to be lost. Then again, I didn't have to live there. I was going back to America.

Eighteen months after I left Russia, in August 1991, the worst fears of the students I had spent time with in the hallway at Moscow State University were realized. A group of hard-line communists, dubbed the "Gang of Eight," attempted to wrest control of the Soviet Union from Gorbachev by declaring a state of emergency. This would have allowed the use of the military on Moscow's streets. Thankfully the coup was bloodless and failed in just two days. The military was never deployed. This event, the "August Coup," is regarded as the beginning of the end of communism and the Soviet Union.

Three months after the coup attempt, in the winter of 1991, the premier issue of Montage was released. It was spectacularly anti-climatic. The mystery of the Soviet Union had already diminished, and all of the original Montage staff had moved on. I had left a month after our return to the United States. Mark and Susan had turned Montage into more of a journal, like The New Yorker, than a periodical that featured photography, like National Geographic. That didn't suit me or my career. After I turned over three binders full of my photographs from Russia, we parted amicably.

Fortunately, the press exposure that Montage received before we left for Russia had captured the attention of many magazine editors. A few of them were kind enough to take a chance and send me on photography assignments around the globe. With each trip, I screwed up less and learned a bit more.

A second issue of Montage was released. No one from the original staff was involved in its production. A few months later there was an announcement that the magazine was going to be shuttered. The news struck me with a pang of nostalgia.

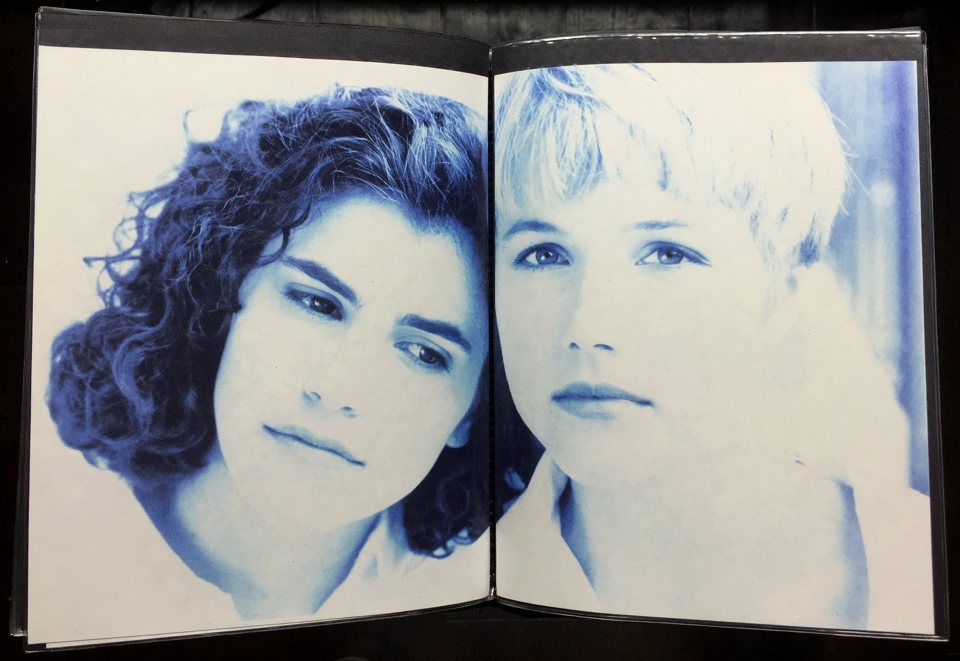

I found an outtake version the image below in a box I dug out of my closet, it was overexposed almost to the point of transparency. I didn't think twice about it, but a close friend, Michelle Hiller, found the photograph compelling. If only it was darker. It was then I remembered that I had bracketed the exposure and a good version existed in the Montage office, in the massive collection I turned in at the end of the assignment. I could break in and steal it back. Michelle and I both laughed.

A few weeks later, I was in Palo Alto with my friend Kimberley. We were a bottle of wine into a rainy evening. I told her about the picture, Muscovites walking into the mist. At the time I took the photograph, I was too inexperienced to recognize it as an epic image, perfect for Vladimir Vyatkin's "mood of Russia" assignment. Now it was destined to get hauled away with the lamps, chairs, and computers when the office was cleared out. Kimberley suggested that we should drive to the Stanford campus and break into the magazine's office.

We both laughed.

One glass later and we were in the car in the rain a hundred yards up the road from the Montage office.

I was soaking wet trying to remember the combination for the realtor's box that held the office key. I couldn't get it. On the side of the portable office was a window. I pushed, bowing it just enough to shake the latch loose.

Inside the office, I found the three massive binders containing all the slides I shot in Russia. I started flipping pages, pulling chromes to take with me. I felt a bit like a drunken spy until I saw the shadow of the front window blinds skate across the wall. Outside a police car had pulled up, training it's headlights on the office. My adrenalin surged and a wave of sobriety washed over me.

As the squawking police radios closed in, the air of mischievousness around the escapade evaporated. I had crossed a criminal line, I was about to get arrested, I was scared, and yet, I felt bizarrely compelled to continue searching for the mist image.

The picture was deep in pages of the third binder. It stood out like a lump of gold on a pebbled stream bed. I pulled it, added it to the other fifty slides I'd collected, and wrapped them all up in a garbage bag for the rain. Then I put the binders away and started conjuring a plan to get out unnoticed.

Outside another police car pulled up.

After a few minutes of panicking, I had a thought. My name undoubtedly existed on some document, somewhere in that office. Furthermore, I was stealing my own images, easily proved by the copyright name-stamp on the border of each of the slides. My presence in the office could plausibly be explained. Escape was simple: stride the through police gauntlet like I belonged there, then talk my way out of the situation when they stopped me.

Mildly lightheaded, I opened the front door, casually descended the metal steps, and walked straight toward the glaring headlights. No one said a word. I made it past the idling police cars and looked back through the downpour at the brightly illuminated cluster of portables. Two police officers were standing in the open doorway of another office. They had a student in handcuffs. He had broken in around the same time as me but, unfortunately for him, his office was alarmed. I just kept walking until I got back to the car where I pounded on the window. Kimberley had fallen asleep.

The mist image was published a few months later with an article, "The Ghost of Communism," about the coup attempt in the Soviet Union, the removal of Gorbachev, the collapse of communism, and the rise of Boris Yeltsin as the new leader of Russia. My photo took on a legendary status that radically elevated me as a photographer, it was the right photo at just the right time. Had it come into the public view six months later, the photo would've received little if any attention. The mystique surrounding the Soviet Union had completely disappeared from the American zeitgeist. I thought back to Novosti, to what Vladimir had said: "The journey to the truth is never obvious."

•••